What Mid-eighteenth-century Act Restricted The Supply Of Money In The North American Colonies?

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to improve this chapter.*

- I. Introduction

- II. Consumption and Trade in the British Atlantic

- III. Slavery, Anti-Slavery and Atlantic Exchange

- IV. Pursuing Political, Religious and Individual Freedom

- V. Seven Years' War

- VI. Pontiac's War

- VII. Conclusion

- VIII. Primary Sources

- IX. Reference Material

I. Introduction

Eighteenth-century American culture moved in competing directions. Commercial, military, and cultural ties between Great Britain and the North American colonies tightened while a new distinctly American culture began to form and bind together colonists from New Hampshire to Georgia. Immigrants from other European nations meanwhile combined with Native Americans and enslaved Africans to create an increasingly diverse colonial population. All—men and women, European, Native American, and African—led distinct lives and wrought new distinct societies. While life in the thirteen colonies was shaped in part by English practices and participation in the larger Atlantic World, emerging cultural patterns increasingly transformed North America into something wholly different.

II. Consumption and Trade in the British Atlantic

Transatlantic trade greatly enriched Britain, but it also created high standards of living for many North American colonists. This two-way relationship reinforced the colonial feeling of commonality with British culture. It was not until trade relations, disturbed by political changes and the demands of warfare, became strained in the 1760s that colonists began to question these ties.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, improvements in manufacturing, transportation, and the availability of credit increased the opportunity for colonists to purchase consumer goods. Instead of making their own tools, clothes, and utensils, colonists increasingly purchased luxury items made by specialized artisans and manufacturers. As the incomes of Americans rose and the prices of these commodities fell, these items shifted from luxuries to common goods. The average person's ability to spend money on consumer goods became a sign of their respectability. Historians have called this process the "consumer revolution."1

Joseph Highmore, The Harlowe Family, from Samuel Richardson's "Clarissa," 1745–1747. Wikimedia.

Britain relied on the colonies as a source of raw materials, such as lumber and tobacco. Americans engaged with new forms of trade and financing that increased their ability to buy British-made goods. But the ways in which colonists paid for these goods varied sharply from those in Britain. When settlers first arrived in North America, they typically carried very little hard or metallic British money with them. Discovering no precious metals (and lacking the Crown's authority to mint coins), colonists relied on barter and nontraditional forms of exchange, including everything from nails to the wampum used by Native American groups in the Northeast. To deal with the lack of currency, many colonies resorted to "commodity money," which varied from place to place. In Virginia, for example, the colonial legislature stipulated a rate of exchange for tobacco, standardizing it as a form of money in the colony. Commodities could be cumbersome and difficult to transport, so a system of notes developed. These notes allowed individuals to deposit a certain amount of tobacco in a warehouse and receive a note bearing the value of the deposit that could be traded as money. In 1690, colonial Massachusetts became the first place in the Western world to issue paper bills to be used as money.2 These notes, called bills of credit, were issued for finite periods of time on the colony's credit and varied in denomination.

While these notes provided colonists with a much-needed medium for exchange, it was not without its problems. Currency that worked in Virginia might be worthless in Pennsylvania. Colonists and officials in Britain debated whether it was right or desirable to use mere paper, as opposed to gold or silver, as a medium of exchange. Paper money tended to lose value quicker than coins and was often counterfeited. These problems, as well as British merchants' reluctance to accept depreciated paper notes, caused the Board of Trade to restrict the uses of paper money in the Currency Acts of 1751 and 1763. Paper money was not the only medium of exchange, however. Colonists also used metal coins. Barter and the extension of credit—which could take the form of bills of exchange, akin to modern-day personal checks—remained important forces throughout the colonial period. Still, trade between colonies was greatly hampered by the lack of standardized money.

Businesses on both sides of the Atlantic advertised both their goods and promises of obtaining credit. The consistent availability of credit allowed families of modest means to buy consumer items previously available only to elites. Cheap consumption allowed middle-class Americans to match many of the trends in clothing, food, and household décor that traditionally marked the wealthiest, aristocratic classes. Provincial Americans, often seen by their London peers as less cultivated or "backwater," could present themselves as lords and ladies of their own communities by purchasing and displaying British-made goods. Visiting the home of a successful businessman in Boston, John Adams described "the Furniture, which alone cost a thousand Pounds sterling. A seat it is for a noble Man, a Prince. The Turkey Carpets, the painted Hangings, the Marble Table, the rich Beds with crimson Damask Curtains and Counterpins, the beautiful Chimney Clock, the Spacious Garden, are the most magnificent of any thing I have seen."3 But many Americans worried about the consequences of rising consumerism. A writer for the Boston Evening Post remarked on this new practice of purchasing status: "For 'tis well known how Credit is a mighty inducement with many People to purchase this and the other Thing which they may well enough do without."4 Americans became more likely to find themselves in debt, whether to their local shopkeeper or a prominent London merchant, creating new feelings of dependence.

Of course, the thirteen continental colonies were not the only British colonies in the Western Hemisphere. In fact, they were considerably less important to the Crown than the sugar-producing islands of the Caribbean, including Jamaica, Barbados, the Leeward Islands, Grenada, St. Vincent, and Dominica. These British colonies were also inextricably connected to the continental colonies. Caribbean plantations dedicated nearly all of their land to the wildly profitable crop of sugarcane, so North American colonies sold surplus food and raw materials to these wealthy island colonies. Lumber was in high demand, especially in Barbados, where planters nearly deforested the island to make room for sugar plantations. To compensate for a lack of lumber, Barbadian colonists ordered house frames from New England. These prefabricated frames were sent via ships from which planters transported them to their plantations. Caribbean colonists also relied on the continental colonies for livestock, purchasing cattle and horses. The most lucrative exchange was the slave trade.

Connections between the Caribbean and North America benefited both sides. Those living on the continent relied on the Caribbean colonists to satisfy their craving for sugar and other goods like mahogany. British colonists in the Caribbean began cultivating sugar in the 1640s, and sugar took the Atlantic World by storm. In fact, by 1680, sugar exports from the tiny island of Barbados valued more than the total exports of all the continental colonies.5 Jamaica, acquired by the Crown in 1655, surpassed Barbados in sugar production toward the end of the seventeenth century. North American colonists, like Britons around the world, craved sugar to sweeten their tea and food. Colonial elites also sought to decorate their parlors and dining rooms with the silky, polished surfaces of rare mahogany as opposed to local wood. While the bulk of this in-demand material went to Britain and Europe, New England merchants imported the wood from the Caribbean, where it was then transformed into exquisite furniture for those who could afford it.

John Hinton, "A representation of the sugar-cane and the art of making sugar," 1749. Library of Congress.

These systems of trade all existed with the purpose of enriching Great Britain. To ensure that profits ended up in Britain, Parliament issued taxes on trade under the Navigation Acts. These taxes intertwined consumption with politics. Prior to 1763, Britain found that enforcing the regulatory laws they passed was difficult and often cost them more than the duty revenue they would bring in. As a result, colonists found it relatively easy to violate the law and trade with foreign nations, pirates, or smugglers. Customs officials were easily bribed and it was not uncommon to see Dutch, French, or West Indies ships laden with prohibited goods in American ports. When smugglers were caught, their American peers often acquitted them. British officials estimated that nearly £700,000 worth of illicit goods was brought into the American colonies annually.6 Pirates also helped to perpetuate the illegal trading activities by providing a buffer between merchants and foreign ships.

Beginning with the Sugar Act in 1764, and continuing with the Stamp Act and the Townshend Acts, Parliament levied taxes on sugar, paper, lead, glass, and tea, all products that contributed to colonists' sense of gentility. In response, patriots organized nonimportation agreements and reverted to domestic products. Homespun cloth became a political statement. A writer in the Essex Gazette in 1769 proclaimed, "I presume there never was a Time when, or a Place where, the Spinning Wheel could more influence the Affairs of Men, than at present."7

The consumer revolution fueled the growth of colonial cities. Cities in colonial America were crossroads for the movement of people and goods. One in twenty colonists lived in cities by 1775.8 Some cities grew organically over time, while others were planned from the start. New York's and Boston's seventeenth-century street plans reflected the haphazard arrangement of medieval cities in Europe. In other cities like Philadelphia and Charleston, civic leaders laid out urban plans according to calculated systems of regular blocks and squares. Planners in Annapolis and Williamsburg also imposed regularity and order over their city streets through the placement of government, civic, and educational buildings.

By 1775, Boston, Newport, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston were the five largest cities in British North America. Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and Charleston had populations of approximately 40,000, 25,000, 16,000, and 12,000 people, respectively.9 Urban society was highly stratified. At the base of the social ladder were the laboring classes, which included both enslaved and free people ranging from apprentices to master craftsmen. Next came the middling sort: shopkeepers, artisans, and skilled mariners. Above them stood the merchant elites, who tended to be actively involved in the city's social and political affairs, as well as in the buying, selling, and trading of goods. Enslaved men and women had a visible presence in both northern and southern cities.

The bulk of the enslaved population lived in rural areas and performed agricultural labor. In port cities, enslaved laborers often worked as domestic servants and in skilled trades: distilleries, shipyards, lumberyards, and ropewalks. Between 1725 and 1775, slavery became increasingly significant in the northern colonies as urban residents sought greater participation in the maritime economy. Massachusetts was the first slave-holding colony in New England. New York traced its connections to slavery and the slave trade back to the Dutch settlers of New Netherland in the seventeenth century. Philadelphia also became an active site of the Atlantic slave trade, and enslaved people accounted for nearly 8 percent of the city's population in 1770.10 In southern cities, including Charleston, urban slavery played an important role in the market economy. Enslaved people, both rural and urban, made up the majority of the laboring population on the eve of the American Revolution.

III. Slavery, Anti-Slavery and Atlantic Exchange

Slavery was a transatlantic institution, but it developed distinct characteristics in British North America. By 1750, slavery was legal in every North American colony, but local economic imperatives, demographic trends, and cultural practices all contributed to distinct colonial variants of slavery.

Virginia, the oldest of the English mainland colonies, imported its first enslaved laborers in 1619. Virginia planters built larger and larger estates and guaranteed that these estates would remain intact through the use of primogeniture (in which a family's estate would descend to the eldest male heir) and the entail (a legal procedure that prevented the breakup and sale of estates). This distribution of property, which kept wealth and property consolidated, guaranteed that the great planters would dominate social and economic life in the Chesapeake. This system also fostered an economy dominated by tobacco. By 1750, there were approximately one hundred thousand enslaved Africans in Virginia, at least 40 percent of the colony's total population.11 Most of these enslaved people worked on large estates under the gang system of labor, working from dawn to dusk in groups with close supervision by a white overseer or enslaved "driver" who could use physical force to compel labor.

Virginians used the law to protect the interests of enslavers. In 1705 the House of Burgesses passed its first comprehensive slave code. Earlier laws had already guaranteed that the children of enslaved women would be born enslaved, conversion to Christianity would not lead to freedom, and enslavers could not free their enslaved laborers unless they transported them out of the colony. Enslavers could not be convicted of murder for killing an enslaved person; conversely, any Black Virginian who struck a white colonist would be severely whipped. Virginia planters used the law to maximize the profitability of their enslaved laborers and closely regulate every aspect of their daily lives.

In South Carolina and Georgia, slavery was also central to colonial life, but specific local conditions created a very different system. Georgia was founded a philanthropic group that included James Oglethorpe. The trustees originally banned slavery from the colony. But by 1750, slavery was legal throughout the region. South Carolina had been a slave colony from its founding and, by 1750, was the only mainland colony with a majority enslaved African population. The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, coauthored by the philosopher John Locke in 1669, explicitly legalized slavery from the very beginning. Many early settlers in Carolina were enslavers from British Caribbean sugar islands, and they brought their brutal slave codes with them. Defiant enslaved people could legally be beaten, branded, mutilated, even castrated. In 1740 a new law stated that killing a rebellious enslaved person was not a crime and even the murder of an enslaved person was treated as a minor misdemeanor. South Carolina also banned the freeing of enslaved laborers unless the freed person left the colony.12

Despite this brutal regime, a number of factors combined to give enslaved people in South Carolina more independence in their daily lives. Rice, the staple crop underpinning the early Carolina economy, was widely cultivated in West Africa, and planters commonly requested that merchants sell them enslaved laborers skilled in the complex process of rice cultivation. Enslaved people from Senegambia were particularly prized.13 The expertise of these enslaved people contributed to one of the most lucrative economies in the colonies. The swampy conditions of rice plantations, however, fostered dangerous diseases. Malaria and other tropical diseases spread and caused many enslavers to live away from their plantations. These elites, who commonly owned a number of plantations, typically lived in Charleston town houses to avoid the diseases of the rice fields. West Africans, however, were far more likely to have a level of immunity to malaria (due to a genetic trait that also contributes to higher levels of sickle cell anemia), reinforcing planters' racial belief that Africans were particularly suited to labor in tropical environments.

With plantation owners often far from home, Carolina enslaved laborers had less direct oversight than those in the Chesapeake. Furthermore, many Carolina rice plantations used the task system to organize enslaved laborers. Under this system, enslaved laborers were given a number of specific tasks to complete in a day. Once those tasks were complete, enslaved people often had time to grow their own crops on garden plots allotted by their enslavers. Thriving underground markets allowed enslaved people here a degree of economic autonomy. Enslaved people in Carolina also had an unparalleled degree of cultural autonomy. This autonomy coupled with the frequent arrival of new Africans enabled a culture that retained many African practices.14 Syncretic languages like Gullah and Geechee contained many borrowed African terms, and traditional African basket weaving (often combined with Native American techniques) survives in the region to this day.

This unique Lowcountry culture contributed to the Stono Rebellion in September 1739. On a Sunday morning while planters attended church, a group of about eighty enslaved people set out for Spanish Florida under a banner that read "Liberty!," burning plantations and killing at least twenty white settlers as they marched. They were headed for Fort Mose, a free Black settlement on the Georgia-Florida border, emboldened by the Spanish Empire's offer of freedom to anyone enslaved by the English. The local militia defeated the rebels in battle, captured and executed many of the enslaved people, and sold others to the sugar plantations of the West Indies. Though the rebellion was ultimately unsuccessful, it was a violent reminder that enslaved people would fight for freedom.

Slavery was also an important institution in the mid-Atlantic colonies. While New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania never developed plantation economies, enslaved laborers were often employed on larger farms growing cereal grains. Enslaved Africans worked alongside European tenant farmers on New York's Hudson Valley "patroonships," huge tracts of land granted to a few early Dutch families. As previously mentioned, enslaved people were also a common sight in Philadelphia, New York City, and other ports where they worked in the maritime trades and domestic service. New York City's economy was so reliant on slavery that over 40 percent of its population was enslaved by 1700, while 15 to 20 percent of Pennsylvania's colonial population was enslaved by 1750.15 In New York, the high density of enslaved people and a particularly diverse European population increased the threat of rebellion. A 1712 slave rebellion in New York City resulted in the deaths of nine white colonists. In retribution, twenty-one enslaved people were executed and six others died by suicide before they could be burned alive. In 1741, authorities uncovered another planned rebellion by enslaved Africans and poor Black and white men. Panic unleashed a witch hunt that only stopped after thirty-two Black men, both enslaved and free, were executed alongside five poor white men. Another seventy were deported, likely to the sugarcane fields of the West Indies.16

Increasingly uneasy about the growth of slavery in the region, Quakers were the first group to turn against slavery. Quaker beliefs in radical nonviolence and the fundamental equality of all human souls made slavery hard to justify. Most commentators argued that slavery originated in war, where captives were enslaved rather than executed. To pacifist Quakers, then, the very foundation of slavery was illegitimate. Furthermore, Quaker belief in the equality of souls challenged the racial basis of slavery. By 1758, Quakers in Pennsylvania disowned members who engaged in the slave trade, and by 1772 slave-owning Quakers could be expelled from their meetings. These local activities in Pennsylvania had broad implications as the decision to ban slavery and slave trading was debated in Quaker meetings throughout the English-speaking world. The free Black population in Philadelphia and other northern cities also continually agitated against slavery.

Slavery as a system of labor never took off in Massachusetts, Connecticut, or New Hampshire, though it was legal throughout the region. The absence of cash crops like tobacco or rice minimized the economic use of slavery. In Massachusetts, only about 2 percent of the population was enslaved as late as the 1760s. The few enslaved people in the colony were concentrated in Boston along with a sizable free Black community that made up about 10 percent of the city's population.17 While slavery itself never really took root in New England, the slave trade was a central element of the region's economy. Every major port in the region participated to some extent in the transatlantic trade—Newport, Rhode Island, alone had at least 150 ships active in the trade by 1740—and New England also provided foodstuffs and manufactured goods to West Indian plantations.18

IV. Pursuing Political, Religious and Individual Freedom

Consumption, trade, and slavery drew the colonies closer to Great Britain, but politics and government split them further apart. Democracy in Europe more closely resembled oligarchies rather than republics, with only elite members of society eligible to serve in elected positions. Most European states did not hold regular elections, with Britain and the Dutch Republic being the two major exceptions. However, even in these countries, only a tiny portion of males could vote. In the North American colonies, by contrast, white male suffrage was far more widespread. In addition to having greater popular involvement, colonial government also had more power in a variety of areas. Assemblies and legislatures regulated businesses, imposed new taxes, cared for the poor in their communities, built roads and bridges, and made most decisions concerning education. Colonial Americans sued often, which in turn led to more power for local judges and more prestige in jury service. Thus, lawyers became extremely important in American society and in turn played a greater role in American politics.

American society was less tightly controlled than European society. This led to the rise of various interest groups, each at odds with the other. These various interest groups arose based on commonalities in various areas. Some commonalities arose over class-based distinctions, while others were due to ethnic or religious ties. One of the major differences between modern politics and colonial political culture was the lack of distinct, stable political parties. The most common disagreement in colonial politics was between the elected assemblies and the royal governor. Generally, the various colonial legislatures were divided into factions who either supported or opposed the current governor's political ideology.

Political structures in the colonies fell under one of three main categories: provincial (New Hampshire, New York, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia), proprietary (Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, and Maryland), and charter (Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut). Provincial colonies were the most tightly controlled by the Crown. The British king appointed all provincial governors and these Crown governors could veto any decision made by their colony's legislative assemblies. Proprietary colonies had a similar structure, with one important difference: governors were appointed by a lord proprietor, an individual who had purchased or received the rights to the colony from the Crown. Proprietary colonies therefore often had more freedoms and liberties than other North American colonies. Charter colonies had the most complex system of government: they were formed by political corporations or interest groups that drew up a charter clearly delineating powers between the executive, legislative, and judiciary branches of government. Rather than having appointed governors, charter colonies elected their own from among property-owning men in the colony.

Nicholas Scull, "To the mayor, recorder, aldermen, common council, and freemen of Philadelphia this plan of the improved part of the city surveyed and laid down by the late Nicholas Scull," Philadelphia, 1762. Library of Congress.

After the governor, colonial government was broken down into two main divisions: the council and the assembly. The council was essentially the governor's cabinet, often composed of prominent individuals within the colony, such as the head of the militia or the attorney general. The governor appointed these men, although the appointments were often subject to approval from Parliament. The assembly was composed of elected, property-owning men whose official goal was to ensure that colonial law conformed to English law. The colonial assemblies approved new taxes and the colonial budgets. However, many of these assemblies saw it as their duty to check the power of the governor and ensure that he did not take too much power within colonial government. Unlike Parliament, most of the men who were elected to an assembly came from local districts, with their constituency able to hold their elected officials accountable to promises made.

An elected assembly was an offshoot of the idea of civic duty, the notion that men had a responsibility to support and uphold the government through voting, paying taxes, and service in the militia. Americans firmly accepted the idea of a social contract, the idea that government was put in place by the people. Philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes and John Locke pioneered this idea, and there is evidence to suggest that these writers influenced the colonists. While in practice elites controlled colonial politics, in theory many colonists believed in the notion of equality before the law and opposed special treatment for any members of colonial society.

Whether African Americans, Native Americans, and women would be included in this notion of equality before the law was far less clear. Women's role in the family became particularly complicated. Many historians view this period as a significant time of transition.19 Anglo-American families during the colonial period differed from their European counterparts. Widely available land and plentiful natural resources allowed for greater fertility and thus encouraged more people to marry earlier in life. Yet while young marriages and large families were common throughout the colonial period, family sizes started to shrink by the end of the 1700s as wives asserted more control over their own bodies.

New ideas governing romantic love helped change the nature of husband-wife relationships. Deriving from sentimentalism, a contemporary literary movement, many Americans began to view marriage as an emotionally fulfilling relationship rather than a strictly economic partnership. Referring to one another as "Beloved of my Soul" or "My More Than Friend," newspaper editor John Fenno and his wife Mary Curtis Fenno illustrate what some historians refer to as the "companionate ideal."20 While away from his wife, John felt a "vacuum in my existence," a sentiment returned by Mary's "Doting Heart."21 Indeed, after independence, wives began to not only provide emotional sustenance to their husbands but inculcate the principles of republican citizenship as "republican wives."22

Marriage opened up new emotional realms for some but remained oppressive for others. For the millions of Americans bound in chattel slavery, marriage remained an informal arrangement rather than a codified legal relationship. For white women, the legal practice of coverture meant that women lost all their political and economic rights to their husband. Divorce rates rose throughout the 1790s, as did less formal cases of abandonment. Newspapers published advertisements by deserted men and women denouncing their partners. Known as "elopement notices," they cataloged the misbehaviors of deviant spouses, such as wives' "indecent manner," a way of implying sexual impropriety. As violence and inequality continued in many American marriages, wives in return highlighted their husbands' "drunken fits" and violent rages. One woman noted that her partner "presented his gun at my breast . . . and swore he would kill me."23

That couples would turn to newspapers as a source of expression illustrates the importance of what historians call print culture.24 Print culture includes the wide range of factors contributing to how books and other printed objects are made, including the relationship between the author and the publisher, the technical constraints of the printer, and the tastes of readers. In colonial America, regional differences in daily life impacted the way colonists made and used printed matter. However, all the colonies dealt with threats of censorship and control from imperial supervision. In particular, political content stirred the most controversy.

From the establishment of Virginia in 1607, printing was either regarded as unnecessary given such harsh living conditions or actively discouraged. The governor of Virginia, Sir William Berkeley, summed up the attitude of the ruling class in 1671: "I thank God there are no free schools nor printing . . . for learning has brought disobedience, and heresy . . . and printing has divulged them."25 Ironically, the circulation of handwritten tracts contributed to Berkeley's undoing. The popularity of Nathaniel Bacon's uprising was in part due to widely circulated tracts questioning Berkeley's competence. Berkeley's harsh repression of Bacon's Rebellion was equally well documented. It was only after Berkeley's death in 1677 that the idea of printing in the southern colonies was revived. William Nuthead, an experienced English printer, set up shop in 1682, although the next governor of the colony, Thomas Culpeper, forbade Nuthead from completing a single project. It wasn't until William Parks set up his printing shop in Annapolis in 1726 that the Chesapeake had a stable local trade in printing and books.

Print culture was very different in New England. Puritans had a respect for print from the beginning. Unfortunately, New England's authors were content to publish in London, making the foundations of Stephen Daye's first print shop in 1639 very shaky. Typically, printers made their money from printing sheets, not books to be bound. The case was similar in Massachusetts, where the first printed work was a Freeman's Oath.26 The first book was not issued until 1640, the Bay Psalm Book, of which eleven known copies survive. Daye's contemporaries recognized the significance of his printing, and he was awarded 140 acres of land. The next large project, the first Bible to be printed in America, was undertaken by Samuel Green and Marmaduke Johnson and published in 1660. That same year, the Eliot Bible, named for its translator John Eliot, was printed in the Natick dialect of the local Algonquin tribes.

Massachusetts remained the center of colonial printing for a hundred years, until Philadelphia overtook Boston in 1770. Philadelphia's rise as the printing capital of the colonies began with two important features: first, the arrival of Benjamin Franklin, a scholar and businessman, in 1723, and second, waves of German immigrants who created a demand for a German-language press. From the mid-1730s, Christopher Sauer, and later his son, met the demand for German-language newspapers and religious texts. Nevertheless, Franklin was a one-man culture of print, revolutionizing the book trade in addition to creating public learning initiatives such as the Library Company and the Academy of Philadelphia. His Autobiography offers one of the most detailed glimpses of life in an eighteenth-century print shop. Franklin's Philadelphia enjoyed a flurry of newspapers, pamphlets, and books for sale. The flurry would only grow in 1776 when the Philadelphia printer Robert Bell issued hundreds of thousands of copies of Thomas Paine's revolutionary Common Sense.

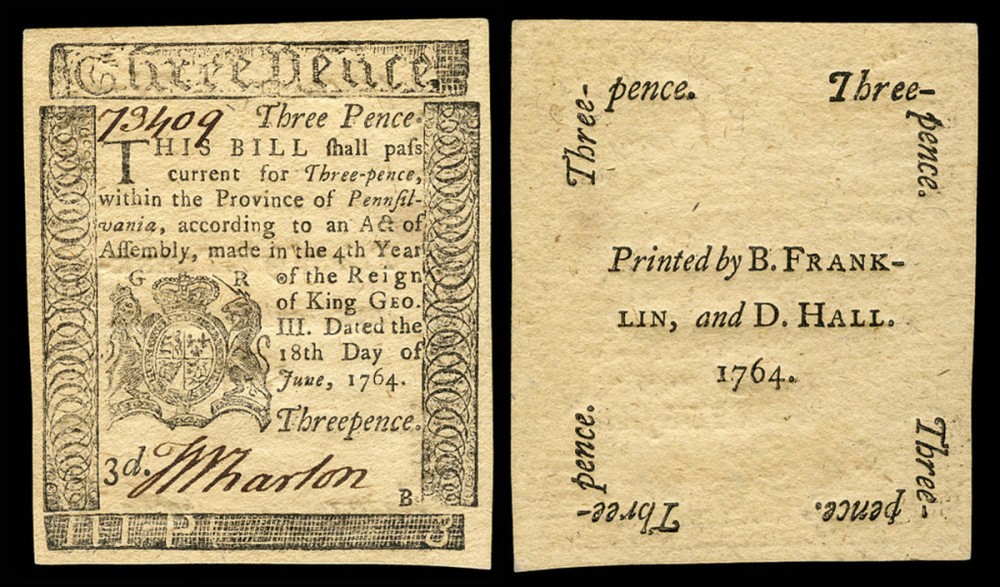

Benjamin Franklin and David Hall, printers, Pennsylvania Currency, 1764. Wikimedia.

Debates on religious expression continued throughout the eighteenth century. In 1711, a group of New England ministers published a collection of sermons titled Early Piety. The most famous minister, Increase Mather, wrote the preface. In it he asked the question, "What did our forefathers come into this wilderness for?"27 His answer was simple: to test their faith against the challenges of America and win. The grandchildren of the first settlers had been born into the comfort of well-established colonies and worried that their faith had suffered. This sense of inferiority sent colonists looking for a reinvigorated religious experience. The result came to be known as the Great Awakening.

Only with hindsight does the Great Awakening look like a unified movement. The first revivals began unexpectedly in the Congregational churches of New England in the 1730s and then spread through the 1740s and 1750s to Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists in the rest of the thirteen colonies. Different places at different times experienced revivals of different intensities. Yet in all of these communities, colonists discussed the same need to strip their lives of worldly concerns and return to a more pious lifestyle. The form it took was something of a contradiction. Preachers became key figures in encouraging individuals to find a personal relationship with God.

The first signs of religious revival appeared in Jonathan Edwards' congregation in Northampton, Massachusetts. Edwards was a theologian who shared the faith of the early Puritan settlers. In particular, he believed in the idea of predestination, in which God had long ago decided who was damned and who was saved. However, Edwards worried that his congregation had stopped searching their souls and were merely doing good works to prove they were saved. With a missionary zeal, Edwards preached against worldly sins and called for his congregation to look inward for signs of God's saving grace. His most famous sermon was "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God." Suddenly, in the winter of 1734, these sermons sent his congregation into violent convulsions. The spasms first appeared among known sinners in the community. Over the next six months the physical symptoms spread to half of the six hundred-person congregation. Edwards shared the work of his revival in a widely circulated pamphlet.

Over the next decade itinerant preachers were more successful in spreading the spirit of revival around America. These preachers had the same spiritual goal as Edwards but brought with them a new religious experience. They abandoned traditional sermons in favor of outside meetings where they could whip the congregation into an emotional frenzy to reveal evidence of saving grace. Many religious leaders were suspicious of the enthusiasm and message of these revivals, but colonists flocked to the spectacle.

![George Whitefield is seen carried by a mob. Two women hoist his legs, one labeled Hypocrisy and the other Deceit. At the bottom a poem reads, Once in an Age that Pest of common sense, enthusiasm revives his old pretence. Clad like simplicity, he stalks along, and draws behind him the dreaded throng. Lives like a comet his protracted twin and warns the world till he returns again. With doctrine borrowed from the [unclear] and journal copyed gravely from George Fox. He fetches forth the sin passages of sin, and sighing sucks the pious woodcocks in. When one trap fails he fabrics new efforts, while Janus-faced hypocrisy supports. The plot still thickens when the plays begun as thirty nine approaches forty one. The baleful consequence our fears avow for what was Peters once is WH-Dnow.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/Great-Awakening-1000x772.jpg)

George Whitefield is shown supported by two women, "Hypocrisy" and "Deceit". The image also includes other visual indications of the engraver's disapproval of Whitefield, including a monkey and jester's staff in the right-hand corner. C. Corbett, publisher, "Enthusiasm display'd: or, the Moor Fields congregation," 1739. Library of Congress.

The most famous itinerant preacher was George Whitefield. According to Whitefield, the only type of faith that pleased God was heartfelt. The established churches too often only encouraged apathy. "The Christian World is dead asleep," Whitefield explained. "Nothing but a loud voice can awaken them out of it."28 He would be that voice. Whitefield was a former actor with a dramatic style of preaching and a simple message. Thundering against sin and for Jesus Christ, Whitefield invited everyone to be born again. It worked. Through the 1730s he traveled from New York to South Carolina converting ordinary men, women, and children. "I have seen upwards of a thousand people hang on his words with breathless silence," wrote a socialite in Philadelphia, "broken only by an occasional half suppressed sob."29 A farmer recorded the powerful impact this rhetoric could have: "And my hearing him preach gave me a heart wound; by God's blessing my old foundation was broken up, and I saw that my righteousness would not save me."30 The number of people trying to hear Whitefield's message was so large that he preached in the meadows at the edges of cities. Contemporaries regularly testified to crowds of thousands and in one case over twenty thousand in Philadelphia. Whitefield and the other itinerant preachers had achieved what Edwards could not: making the revivals popular.

Ultimately the religious revivals became a victim of the preachers' success. As itinerant preachers became more experimental, they alienated as many people as they converted. In 1742, one preacher from Connecticut, James Davenport, persuaded his congregation that he had special knowledge from God. To be saved they had to dance naked in circles at night while screaming and laughing. Or they could burn the books he disapproved of. Either way, such extremism demonstrated for many that revivalism had gone wrong.31 A divide appeared by the 1740s and 1750s between "New Lights," who still believed in a revived faith, and "Old Lights," who thought it was deluded nonsense.

By the 1760s, the religious revivals had petered out; however, they left a profound impact on America. Leaders like Edwards and Whitefield encouraged individuals to question the world around them. This idea reformed religion in America and created a language of individualism that promised to change everything else. If you challenged the Church, what other authority figures might you question? The Great Awakening provided a language of individualism, reinforced in print culture, which reappeared in the call for independence. While prerevolutionary America had profoundly oligarchical qualities, the groundwork was laid for a more republican society. However, society did not transform easily overnight. It would take intense, often physical, conflict to change colonial life.

V. Seven Years' War

Of the eighty-seven years between the Glorious Revolution (1688) and the American Revolution (1775), Britain was at war with France and French-allied Native Americans for thirty-seven of them. These were not wars in which European soldiers fought other European soldiers. American militiamen fought for the British against French Catholics and their Native American allies in all of these engagements. Warfare took a physical and spiritual toll on British colonists. British towns located on the border between New England and New France experienced intermittent raiding by French-allied Native Americans. Raiding parties destroyed houses and burned crops, but they also took captives. They brought these captives to French Quebec, where some were ransomed back to their families in New England and others converted to Catholicism and remained in New France. In this sense, Catholicism threatened to capture Protestant lands and souls.

France and Britain feuded over the boundaries of their respective North American empires. The feud turned bloody in 1754 when a force of British colonists and Native American allies, led by young George Washington, killed a French diplomat. This incident led to a war, which would become known as the Seven Years' War or the French and Indian War. In North America, the French achieved victory in the early portion of this war. They attacked and burned multiple British outposts, such as Fort William Henry in 1757. In addition, the French seemed to easily defeat British attacks, such as General Braddock's attack on Fort Duquesne, and General Abercrombie's attack on Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga) in 1758. These victories were often the result of alliances with Native Americans.

Albert Bobbett, engraver, "Montcalm trying to stop the massacre," c. 1870-1880. Library of Congress.

In Europe, the war did not fully begin until 1756, when British-allied Frederick II of Prussia invaded the neutral state of Saxony. As a result of this invasion, a massive coalition of France, Austria, Russia, and Sweden attacked Prussia and the few German states allied with Prussia. The ruler of Austria, Maria Theresa, hoped to conquer the province of Silesia, which had been lost to Prussia in a previous war. In the European war, the British monetarily supported the Prussians, as well as the minor western German states of Hesse-Kassel and Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel. These subsidy payments enabled the smaller German states to fight France and allowed the excellent Prussian army to fight against the large enemy alliance.

However, as in North America, the early part of the war went against the British. The French defeated Britain's German allies and forced them to surrender after the Battle of Hastenbeck in 1757. That same year, the Austrians defeated the Prussians in the Battle of Kolín and Frederick of Prussia defeated the French at the Battle of Rossbach. The latter battle allowed the British to rejoin the war in Europe. Just a month later, in December 1757, Frederick's army defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Leuthen, reclaiming the vital province of Silesia. In India and throughout the world's oceans, the British and their fleet consistently defeated the French. In June, for instance, Robert Clive and his Indian allies had defeated the French at the Battle of Plassey. With the sea firmly in their control, the British could send additional troops to North America.

These newly arrived soldiers allowed the British to launch new offensives. The large French port and fortress of Louisbourg, in present-day Nova Scotia, fell to the British in 1758. In 1759, British general James Wolfe defeated French general Louis-Joseph de Montcalm in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, outside Quebec City. In Europe, 1759 saw the British defeat the French at the Battle of Minden and destroy large portions of the French fleet. The British referred to 1759 as the annus mirabilis or the year of miracles. These victories brought about the fall of French Canada, and war in North America ended in 1760 with the British capture of Montreal. The British continued to fight against the Spanish, who entered the war in 1762. In this war, the Spanish successfully defended Nicaragua against British attacks but were unable to prevent the conquest of Cuba and the Philippines.

The Seven Years' War ended with the peace treaties of Paris and Hubertusburg in 1763. The British received much of Canada and North America from the French, while the Prussians retained the important province of Silesia. This gave the British a larger empire than they could control, which contributed to tensions that would lead to revolution. In particular, it exposed divisions within the newly expanded empire, including language, national affiliation, and religious views. When the British captured Quebec in 1760, a newspaper distributed in the colonies to celebrate the event boasted: "The time will come, when Pope and Friar/Shall both be roasted in the fire/When the proud Antichristian whore/will sink, and never rise more."32

American colonists rejoiced over the defeat of Catholic France and felt secure that the Catholics in Quebec could no longer threaten them. Of course, some American colonies had been a haven for religious minorities since the seventeenth century. Catholic Maryland, for example, evidenced early religious pluralism. But practical toleration of Catholics existed alongside virulent anti-Catholicism in public and political arenas. It was a powerful and enduring rhetorical tool borne out of warfare and competition between Britain and France.

In part because of constant conflict with Catholic France, Britons on either side of the Atlantic rallied around Protestantism. British ministers in England called for a coalition to fight French and Catholic empires. Missionary organizations such as the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel were founded at the turn of the eighteenth century to evangelize Native Americans and limit Jesuit conversions. The Protestant revivals of the so-called Great Awakening crisscrossed the Atlantic and founded a participatory religious movement during the 1730s and 1740s that united British Protestant churches. Preachers and merchants alike urged greater Atlantic trade to bind the Anglophone Protestant Atlantic through commerce and religion.

VI. Pontiac's War

Relationships between colonists and Native Americans were complex and often violent. In 1761, Neolin, a prophet, received a vision from his religion's main deity, known as the Master of Life. The Master of Life told Neolin that the only way to enter heaven would be to cast off the corrupting influence of Europeans by expelling the British: "This land where ye dwell I have made for you and not for others. Whence comes it that ye permit the Whites upon your lands. . . . Drive them out, make war upon them."33 Neolin preached the avoidance of alcohol, a return to traditional rituals, and unity among Indigenous people to his disciples, including Pontiac, an Ottawa leader.

Pontiac took Neolin's words to heart and sparked the beginning of what would become known as Pontiac's War. At its height, the uprising included Native peoples from the territory between the Great Lakes, the Appalachians, and the Mississippi River. Though Pontiac did not command all of those participating in the war, his actions were influential in its development. Pontiac and three hundred warriors sought to take Fort Detroit by surprise in May 1763, but the plan was foiled, resulting in a six-month siege of the British fort. News of the siege quickly spread and inspired more attacks on British forts and settlers. In May, Native Americans captured Forts Sandusky, St. Joseph, and Miami. In June, a coalition of Ottawas and Ojibwes captured Fort Michilimackinac by staging a game of stickball (lacrosse) outside the fort. They chased the ball into the fort, gathered arms that had been smuggled in by a group of Native American women, and killed almost half of the fort's British soldiers.

Though these Native Americans were indeed responding to Neolin's religious message, there were many other practical reasons for waging war on the British. After the Seven Years' War, Britain gained control of formerly French territory as a result of the Treaty of Paris. Whereas the French had maintained a peaceful and relatively equal relationship with their Native American allies through trade, the British hoped to profit from and impose "order." For example, the French often engaged in the Indigenous practice of diplomatic gift giving. However, British general Jeffrey Amherst discouraged this practice and regulated the trade or sale of firearms and ammunition to Indigenous people. Most Native Americans, including Pontiac, saw this not as frugal imperial policy but preparation for war.

Pontiac's War lasted until 1766. Native American warriors attacked British forts and frontier settlements, killing as many as four hundred soldiers and two thousand settlers.34 Disease and a shortage of supplies ultimately undermined the war effort, and in July 1766 Pontiac met with British official and diplomat William Johnson at Fort Ontario and settled for peace. Though they did not win Pontiac's War, Native Americans succeeded in fundamentally altering the British government's policy. The war made British officials recognize that peace in the West would require royal protection of Native American lands and heavy-handed regulation of Anglo-American trade activity in territory controlled by Native Americans. During the war, the British Crown issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which created the proclamation line marking the Appalachian Mountains as the boundary between the British colonies and land held controlled by Native Americans.

The effects of Pontiac's War were substantial and widespread. The war proved that coercion was not an effective strategy for imperial control, though the British government would continue to employ this strategy to consolidate their power in North America, most notably through the various acts imposed on their colonies. Additionally, the prohibition of Anglo-American settlement in Native American territory, especially the Ohio River Valley, sparked discontent. The French immigrant Michel-Guillaume-Saint-Jean de Crèvecoeur articulated this discontent most clearly in his 1782 Letters from an American Farmer when he asked, "What then is the American, this new man?" In other words, why did colonists start thinking of themselves as Americans, not Britons? Crèvecoeur suggested that America was a melting pot of self-reliant individual landholders, fiercely independent in pursuit of their own interests, and free from the burdens of European class systems. It was an answer many wanted to hear and fit with self-conceptions of the new nation, albeit one that imagined itself as white, male, and generally Protestant.35 The Seven Years' War pushed the thirteen American colonies closer together politically and culturally than ever before. In 1754, at the Albany Congress, Benjamin Franklin suggested a plan of union to coordinate defenses across the continent. Tens of thousands of colonials fought during the war. At the French surrender in 1760, 11,000 British soldiers joined 6,500 militia members drawn from every colony north of Pennsylvania.36 At home, many heard or read sermons that portrayed the war as a struggle between civilizations with liberty-loving Britons arrayed against tyrannical Frenchmen and savage Indigenous people. American colonists rejoiced in their collective victory as a moment of newfound peace and prosperity. After nearly seven decades of warfare they looked to the newly acquired lands west of the Appalachian Mountains as their reward.

The Seven Years' War was tremendously expensive and precipitated imperial reforms on taxation, commerce, and politics. Britain spent over £140 million, an astronomical figure for the day, and the expenses kept coming as new territory required new security obligations. Britain wanted to recoup some of its expenses and looked to the colonies to share the costs of their own security. To do this, Parliament started legislating over all the colonies in a way rarely done before. As a result, the colonies began seeing themselves as a collective group, rather than just distinct entities. Different taxation schemes implemented across the colonies between 1763 and 1774 placed duties on items like tea, paper, molasses, and stamps for almost every kind of document. Consumption and trade, an important bond between Britain and the colonies, was being threatened. To enforce these unpopular measures, Britain implemented increasingly restrictive policies that eroded civil liberties like protection from unlawful searches and jury trials. The rise of an antislavery movement made many colonists worry that slavery would soon be attacked. The moratorium on new settlements in the West after Pontiac's War was yet another disappointment.

VII. Conclusion

By 1763, Americans had never been more united. They fought and they celebrated together. But they also recognized that they were not considered full British citizens, that they were considered something else. Americans across the colonies viewed imperial reforms as threats to the British liberties they saw as their birthright. The Stamp Act Congress of 1765 brought colonial leaders together in an unprecedented show of cooperation against taxes imposed by Parliament, and popular boycotts of British goods created a common narrative of sacrifice, resistance, and shared political identity. A rebellion loomed.

VIII. Primary Sources

1. Boston trader Sarah Knight on her travels in Connecticut, 1704

Sarah Knight traveled from her home in Massachusetts to trade goods. Through her diary, we can get a sense of life during the consumer revolution, as well as some of the prejudices and inequalities that shaped life in eighteenth-century New England.

2. Eliza Lucas letters, 1740-1741

Eliza Lucas was born into a moderately wealthy family in South Carolina. Throughout her life she shrewdly managed her money and greatly added to her family's wealth. These two letters from an unusually intelligent financial manager offer a glimpse into the commercial revolution and social worlds of the early eighteenth century.

3. Jonathan Edwards revives Enfield, Connecticut, 1741

Jonathan Edwards catalyzed the revivals known as the Great Awakening. While Edwards was not the most prolific revivalist of the era—that honor belonged to George Whitefield—he did deliver the most famous sermon of the eighteenth century, commonly called "Sinners in the Hands of Angry God." This excerpt is drawn from the final portion of the sermon, known as the application, where hearers were called to take action.

4. Samson Occom describes his conversion and ministry, 1768

Samson Occom was raised with the traditional spirituality of his Mohegan parents but converted to Christianity during the Great Awakening. He then studied for the ministry and became a missionary, minister, and teacher on Long Island, New York. Despite his successful ministry, Occom struggled to receive the same level of support as white missionaries.

5. Extracts from Gibson Clough's war journal, 1759

Gibson Clough enlisted in the militia during the Seven Years War. His diary shows the experience of soldiers in the conflict, but also reveals the brutal discipline of the British regular army. Soldiers like Clough ended their term of service with pride in their role defending the glory of Britain but also suspicion of the rigid British military.

6. Pontiac calls for war, 1763

Pontiac, an Ottawa war chief, drew on the teachings of the prophet Neolin to rally resistance to European powers. This passage includes Neolin's call that Native Americans abandon ways of life adapted after contact with Europeans.

7. Alibamo Mingo, Choctaw leader, reflects on the British and French, 1765

The end of the Seven Years War brought shockwaves throughout Native American communities. With the French removed from North America, their former Native American allies were forced to adapt quickly. In this document, a Choctaw leader expresses his concern over the new political reality.

8. Blueprint and photograph of Christ Church

Religion played an important role in each of the British colonies – for different reasons. In Virginia, the Anglican church was the official religion of the colonial government and colonists had to attend or be fined, so churches like Christ Church became important sites for political, economic, and social activity that reinforced the dominance of the planter elite. Robert "King" Carter built this church on the site of an earlier one built by his father. The Carter tombs belong to Robert Carter and his first and second wives. The colonial road that stopped at the door of the church went directly to the Carter family estate. Pews corresponded with social status: the highest ranking member of the gentry sat in the pew before the altar, across from the pulpit. Poor whites sat at the back, and enslaved men and women who came to church would have stood or taken the seats closest to the door – cold in winter, hot in summer, and farthest from the preacher. Many churches eventually built separate gallery seating for the enslaved who attended services. These churches were criticized during the Great Awakening, particularly by Baptists, who preached the equality of souls and felt the Anglican church was lacking in religiosity.

9. Royall family, 1741

Colonial elites used clothing, houses, portraits, furniture, and manners to participate in a culture of gentility that they believed placed them on an equal footing with elites in England. Robert Feke's 1741 portrait of the Royall family portrays Isaac Royall Jr. at age 22, just two years after he inherited his father's estate, including the family mansion outside Boston, a sugar plantation on Antigua, and eighteen enslaved African Americans, which helped him become one of the wealthiest men in the colony of Massachusetts. He married Elizabeth McIntosh (wearing blue), aged fifteen at the time of her marriage in 1738, confirming his position among the colonial elite. Their eight-month-old daughter, Elizabeth, holds a coral teething stick with a gold and ivory handle (coral was traditionally believed to ward off evil spirits). Also pictured is Penelope Royall Vassall, Isaac's sister who married a Jamaican planter, and his sister-in-law, Mary McIntosh Palmer. Mary Palmer's pointed finger and Isaac Royall's hand on his hip were poses drawn from other major artistic works and were intended to convey their ease and refinement, while their silken clothes communicated wealth.

IX. Reference Material

This chapter was edited by Nora Slonimsky, with content contributions by Emily Arendt, Ethan R. Bennett, John Blanton, Alexander Burns, Mary Draper, Jamie Goodall, Jane Fiegen Green, Hendrick Isom, Kathryn Lasdow, Allison Madar, Brooke Palmieri, Katherine Smoak, Christopher Sparshott, Ben Wright, and Garrett Wright.

Recommended citation: Emily Arendt et al., "Colonial Society," Nora Slonimsky, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).

Recommended Reading

- Anishanslin, Zara. Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the British Atlantic World. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016.

- Breen, T. H. The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Bushman, Richard L. The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities. New York: Vintage Books, 1992.

- Butler, Jon. Becoming America: The Revolution Before 1776. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Carp, Benjamin L. Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Carté-Engel, Katherine. Religion and Profit: Moravians in Early America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

- Demos, John P. The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America. New York: Vintage Books, 1994.

- Dowd, Gregory Evans. War Under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, and British Empire. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

- Frey, Sylvia R., and Betty Wood. Come Shouting to Zion: African American Protestantism in the American South and British Caribbean to 1830. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

- Hackel, Heidi Brayman, and Catherine E. Kelly, eds. Reading Women: Literacy, Authorship, and Culture in the Atlantic World, 1500–1800. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

- Hancock, David. Citizens of the World: London Merchants and the Integration of the British Atlantic Community, 1735–1785. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Heyrman, Christine. Southern Cross: The Beginnings of the Bible Belt. New York: Knopf, 1997.

- Holton, Woody. Forced Founders: Indians, Debtors, Slaves, and the Making of the American Revolution in Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

- Klepp, Susan E. Revolutionary Conceptions: Women, Fertility, and Family Limitation in America, 1760–1820. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

- Lepore, Jill. New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan. New York: Vintage Books, 2005.

- McConville, Brendan. The King's Three Faces: The Rise and Fall of Royal America, 1688–1776. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

- Merritt, Jane T. At the Crossroads: Indians and Empires on a Mid–Atlantic Frontier, 1700-1763. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- Podruchny, Carolyn. Making the Voyageur World: Travelers and Traders in the North American Fur Trade. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

- Richter, Daniel K. Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

- Sensbach, Jon F. Rebecca's Revival: Creating Black Christianity in the Atlantic World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Sheridan, Richard B. Sugar and Slavery: An Economic History of the British West Indies, 1623–1775. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974.

- Taylor, Alan. The Divided Ground: Indians, Settlers, and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution. New York: Vintage Books, 2006.

- Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth. New York: Knopf, 2001.

- ———. A Midwife's Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785–1812. New York: Knopf, 1990.

- Zabin, Serena R. Dangerous Economies: Status and Commerce in Imperial New York. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011

Notes

- T. H. Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004). [↩]

- Alvin Rabushka, Taxation in Colonial America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008), 360. [↩]

- T. H. Breen, "'Baubles of Britain': The American and Consumer Revolutions of the Eighteenth Century," Past and Present, 119, no. 1 (May 1988): 79. [↩]

- "To the Publisher of the Boston Evening Post," Boston Evening Post, no. 150 (June 6, 1738): 1. [↩]

- Richard B. Sheridan, Sugar and Slavery: An Economic History of the British West Indies, 1623–1775 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974), 144. [↩]

- Archibald Paton Thornton, The Habit of Authority: Paternalism in British History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1966), 123. [↩]

- Cited in Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (New York: Knopf, 2001), 37. [↩]

- Gary B. Nash, The Urban Crucible: The Northern Seaports and the Origins of the American Revolution, Abridged Edition (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), ix. [↩]

- Kenneth T. Jackson and Stanley K. Schultz, Cities in American History (New York: Knopf, 1972), 45. [↩]

- Gary B. Nash, "Slaves and Slave Owners in Colonial Philadelphia," in African Americans in Pennsylvania: Shifting Historical Perspectives, ed. Joe Trotter and Eric Ledell Smith (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997), 49–50. [↩]

- Donald Matthews, Religion in the Old South (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977), 6. [↩]

- Robert Olwell, Masters, Slaves, & Subjects: The Culture of Power in the South Carolina Lowcountry (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998), 67. [↩]

- Daniel C. Littlefield, Rice and Slaves: Ethnicity and the Slave Trade in Colonial South Carolina (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 8. [↩]

- Sylvia R. Frey and Betty Wood, Come Shouting to Zion: African American Protestantism in the American South and British Caribbean to 1830 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998). [↩]

- See Appendix D of Dorothy Schneider and Carl J. Schneider, Slavery in America (New York: Infobase, 2007). [↩]

- Thomas Joseph Davis, A Rumor of Revolt: The "Great Negro Plot" in Colonial New York (New York: Free Press, 1985). [↩]

- U.S. Census Bureau, "Colonial and Pre-Federal Statistics," http://www2.census.gov/prod2/statcomp/documents/CT1970p2-13.pdf, accessed April 24, 2018; James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1999), xiv. [↩]

- Elaine F. Crane, "'The First Wheel of Commerce': Newport, Rhode Island and the Slave Trade, 1760–1776," Slavery and Abolition 1, no. 2 (1980): 178–198. [↩]

- Rosemarie Zagarri, Revolutionary Backlash: Women and Politics in the Early American Republic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007). [↩]

- Lucia McMahon, Mere Equals: The Paradox of Educated Women in the Early American Republic (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012). [↩]

- Fenno-Hoffman Family Papers, Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Anya Jabour, Marriage in the Early Republic: Elizabeth and William Wirt and the Companionate Ideal (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998). [↩]

- Jan Lewis, "The Republican Wife: Virtue and Seduction in the Early Republic," William and Mary Quarterly 44, no. 4 (1987): 689–721. [↩]

- New York Packet, January 9, 1790; New-Jersey Journal, January 20, 1790; Mary Beth Sievens, Stray Wives: Marital Conflict in Early National New England (New York: New York University Press, 2005). [↩]

- Trish Loughran, The Republic in Print: Print Culture in the Age of U.S. Nation-Building, 1770–1870 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007). [↩]

- Cited in David D. Hall, Cultures in Print: Essays in the History of the Book (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996), 99. [↩]

- Hugh Amory and David D. Hall, A History of the Book in America: Volume 1, The Colonial Book in the Atlantic World (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000): 111. [↩]

- John Gillies, Historical Collections Relating to the Remarkable Success of the Gospel and Eminent Instruments Employed in Promoting It, Volume II (Glasgow: Foulis, 1754), 19. [↩]

- George Whitefield, The Works of the Reverend George Whitefield, Vol. I (London: Dilly, 1771), 73. [↩]

- William G. McLoughlin, Revivals, Awakenings, and Reform (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 62. [↩]

- Thomas S. Kidd, George Whitefield: America's Spiritual Founding Father (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014), 131. [↩]

- Leigh Eric Schmidt, "'A Second and Glorious Reformation': The New Light Extremism of Andrew Croswell," William and Mary Quarterly 43, no. 2 (April 1986), 214–244. [↩]

- "Canada Subjected: A New Song" ([n.p., 1760?]), quoted in Thomas Kidd, God of Liberty: A Religious History of the American Revolution (New York: Basic Books, 2010), 29. [↩]

- Daniel K. Richter, Before the Revolution: America's Ancient Pasts (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 403. [↩]

- Gregory Evans Dowd, War Under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, and British Empire (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004). [↩]

- Read de Crèvecoeur's Letters from an American Farmer online at http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/crev/home.html. [↩]

- Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766 (New York: Knopf Doubleday, 2007), 410. [↩]

What Mid-eighteenth-century Act Restricted The Supply Of Money In The North American Colonies?

Source: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/04-colonial-society/

Posted by: nelsonsamostow.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Mid-eighteenth-century Act Restricted The Supply Of Money In The North American Colonies?"

Post a Comment